You may have heard the acronym TEK pop up in conversations recently, but what is it and how do we engage with it?

The term Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) was used widely in the 1980s. It was coined by Western scientists wanting to describe Indigenous Peoples’ knowledge and understanding of the environment (1, 2). The research of TEK has mostly been done by non-native researchers searching to compile facts that can fit into the framework of western science and restoration plans.

Recognizing TEK

TEK is not a simple statement of facts on how plants and animals have been used or revered by Native peoples. Western Science, and Traditional Ecological Knowledge are different frameworks to experience the natural world. Western science uses a linear process of collecting and interpreting data, but that interpretation is still happening from the perspective and world view of the, often non-native, scientist. The format of TEK, presented as facts in the middle of a field guide is a result of non-native scholars taking knowledge from Indigenous peoples without proper credit and often generalizing the information.

When I have encountered information on uses of plants being passed off as TEK for non-native audiences, these generalized ‘facts’ often refer to the First Peoples of the land in past tense. This does not honor the deep relationship between the people and the land, and attempts to erase contemporary Indigenous peoples.

For non-native people to engage with TEK respectfully, we must acknowledge that it is not our information to share. While, as a non-native person, I cannot share ‘fun facts’ on TEK without context and permission of the knowledge holders, I can point others in the direction of Native authors who discuss TEK or towards other ways to learn more such as an Eco Tour with the Duwamish Longhouse. For the Green Seattle Partnership, it has not been until the past 5 years or so that there has been more consideration in centering, and giving credit to, Native voices when discussing TEK. Some groups in the Puget Sound have engaged with TEK for longer, and others are just beginning the conversation now.

My personal understanding of the importance of the recognition and inclusion of Indigenous knowledge began in conversations with family members who have familial connections to Tribes and has continued with friends and colleagues in my academic and professional career. Following the accentuation of present racial and social inequities due to the pandemic, there has been a resurgence of conversation on TEK and tribal involvement with environmental management and restoration.

Due to insurgence of conversation around it and the importance of it, let’s discuss how we can understand and engage with TEK respectfully. At the basis of TEK, is a spiritual, cultural, and communal relationship between Indigenous peoples and the land’s plants and animals. The specifics of TEK vary from Tribe to Tribe, but at the center is a reciprocal relationship with the land (2). Dr. Robin Wall Kimmerer, a Potowatami woman and the author of Braiding Sweetgrass, describes this relationship as being rooted in gratitude for the gifts the land and animals give, and then taking care of them in return. TEK is not just observations and knowledge of plants and animals, but is the basis of culture community, and politics (3).https://native-land.ca/

When we offer a land acknowledgement before a GSP volunteer event or other gathering, we are acknowledging whose land we are on. In doing this, we must also individually recognize the past and current hardships Indigenous communities face because of colonization.

Before we can engage with TEK, we must first acknowledge who holds that knowledge and respect tribes’ autonomy. I cannot begin to understand the depth of Indigenous knowledge without actively becoming an ally to Indigenous peoples, specifically to the tribes whose land I live on. In Seattle, we live on stolen Duwamish Land. We must advocate for justice for Indigenous peoples and the land, while collectively working with them to do this work. Respectfully engaging with TEK includes engaging in land acknowledgement, justice of all forms, and collaboration and partnership with Tribes.

Although Indigenous voices were not centered in the inception of the Green Seattle Partnership, we are now listening to and working with the Duwamish Tribe, Na’ah Illahee, and the United Tribes of All Indians. Centering TEK and allyship in our culture as an organization and a community is necessary. Individually, we can partner with Tribes by contributing regularly to mutual aids funds such as Real Rent Duwamish. The Duwamish tribe is still waiting on recognition by the federal government; you can support the tribe’s efforts by signing their petition, writing letters to your US representatives, and donating.

Respecting TEK

For those of us who are non-native people, we can read the works of Native authors and listen to webinars and seminars given by Native people concerning TEK and the environmental field. We can reflect on the reciprocal relationship that Indigenous knowledge is grounded in and the sacred nature of this knowledge. We can ask ourselves: How can our ways of understanding nature shift? How can we engage in restoration differently? What partnerships can we form to heal our relationship with the land? How can we better listen to the voices of BIPOC communities?

The process of being an ally is a continual one of listening, reflecting, acting and healing. I cannot become an ally of my own community or other BIPOC communities without healing my relationship with the land and coming to terms with inequalities, both past and present. In the 2001 Indigenous Knowledge Conference, Leanna Simpson presented a paper on their observations as an Indigenous women in science. This is their definition of the appropriate use of TEK:

“The appropriate use of Indigenous Knowledge requires Indigenous Peoples, not academic researchers or government personell, but Indigenous Peoples. It is about relationships and context. It requires the recognition of the continued impacts of colonization and colonialism on our lands, peoples and cultures. It requires the voices and input of Aboriginal women, men, youth, Elders and Knowledge Holders. It requires an acknowledgment of power imbalances and the legacy of injustice faced by Aboriginal Peoples. It requires that Indigenous Peoples drive research agendas not outside interests. And most importantly, it requires the respect for Aboriginal jurisdiction over Aboriginal land.”

The National Park Service has compiled a series of webinars and papers entitled “TEK vs Western Science” by both Native and non-native scholars, community members, and scientists. It is a great resource to begin diving into the topic of TEK, you can find it here.

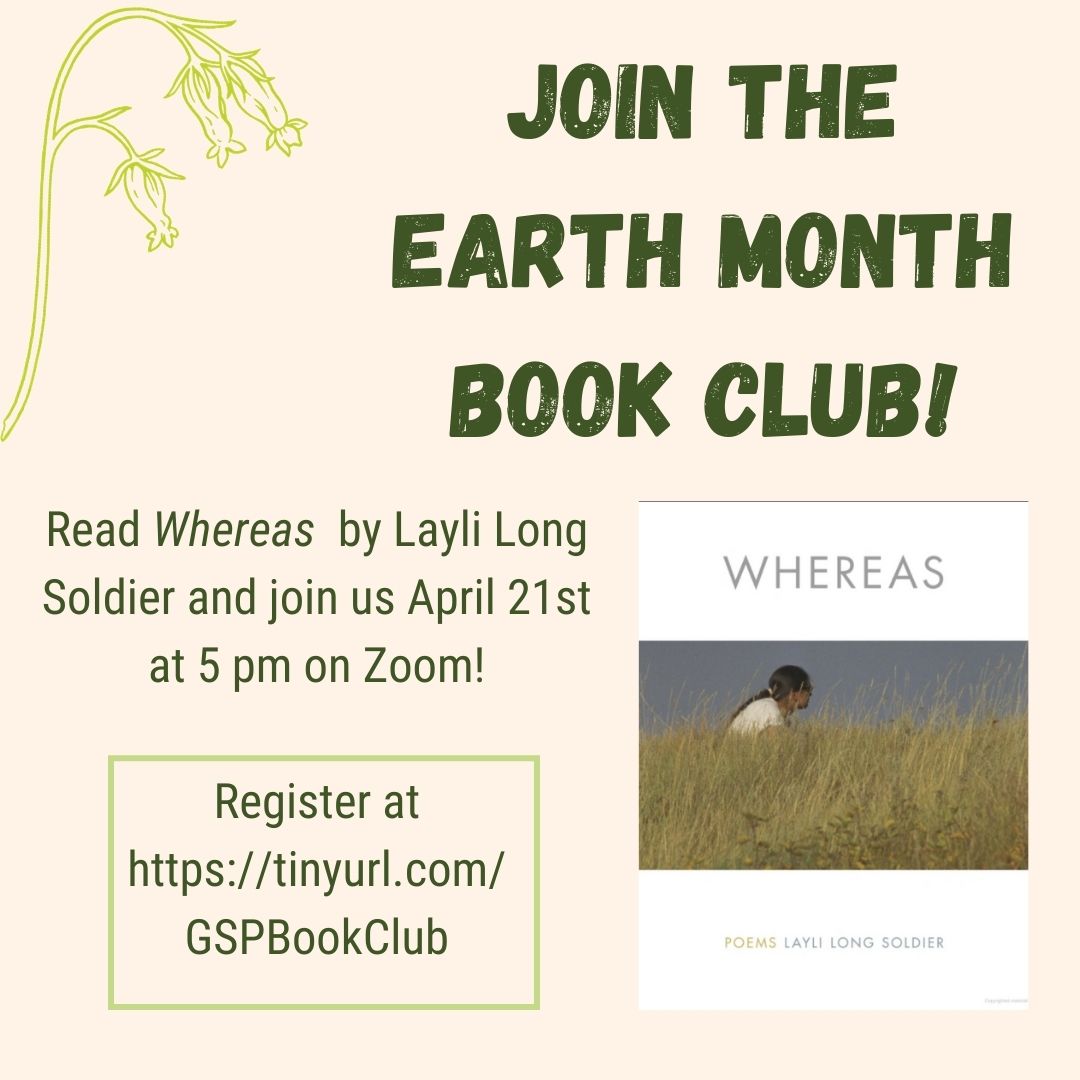

Also check out a book list we compiled by different Indigenous authors from around the world that explore the hardships, history, and knowledge of various Indigenous peoples. We’ve selected one book in particular that we will be discussing in a live virtual event on April 21st, 2021 at 5pm.

This Earth Month as we recognize, respect, and reflect on the resources listed above and other sources you find on TEK, look for ways for you to approach nature differently each day. Often, we get caught up in one issue related to restoration or with the landscape as we recreate. Let’s look at our work, the forest, and the communities we engage with holistically.

Sources

(1) “Traditional Ecological Knowledge in Perspective” Fikret Berkes: https://library.um.edu.mo/ebooks/b10756577a.pdf

(2) “Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Western Science: Projections, Problems, and Potential” Dylan Kelly: https://indigenousnh.com/2020/01/31/traditional-ecological-knowledge-and-western-science-projections-problems-and-potential/

(3) “Weaving Traditional Ecological Knowledge into Biological Education” Robin Wall Kimmerer: https://academic.oup.com/bioscience/article/52/5/432/236145

Trackbacks/Pingbacks